A Brief History of the Carnegie Library

The First Free Public Library in Wakefield

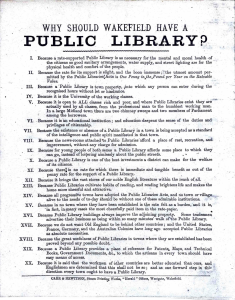

Prior to the opening of the first free public library in Wakefield on Drury Lane in 1906, there had been many calls for one to be built for 30 years, including the establishment of a Public Library Provisional Committee in the 1890s. In March 1894, Mr. Sam Whitaker, one of the committee’s secretaries, drew attention to a new public library that had opened in London for the modest cost of £2,980. He suggested that Wakefield would benefit from a similar library in terms of cost and scale. The 1850 Public Libraries Act gave borough councils with a population of ten thousand or more the power to spend half a penny (old pence) rate on the provision it was for a library and/or museum and its maintenance. However, the adoption of this act was subject to the approval of two-thirds of the ratepayers, so special polls were held to try to establish a public library in Wakefield. The initial plans were rejected due to a lack of funds.

However, in 1904, Wakefield’s Mayor, Henry S. Childe, successfully secured £8,000 from Andrew Carnegie, a Scottish-born philanthropic multi-millionaire, for the construction of a new library. Carnegie, a former ironmaster and successful businessman had previously donated a free library to his hometown of Dunfermline in 1882 after retiring, stating he wished ‘to promote the advancement and diffusion of knowledge’ for all.

Wakefield took advantage of Carnegie’s generosity, as he had a personal fortune of approximately £60m, largely earned from railway development in America with companies such as the Pittsburg Locomotive Works and the Keystone Iron Bridge Company. Carnegie donated around £12m for the establishment of 660 libraries in the UK (2811 worldwide), and Wakefield was one of the chosen boroughs after an application by Mayor Childe in 1902. The funding was provided on the condition that the Public Library Act (1850) was activated, allowing the collection of a penny rate.

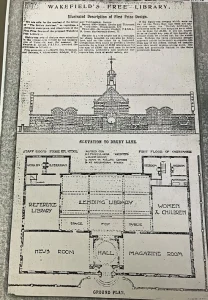

The library’s design was chosen through a competition, with 81 people entering. The award went to architects Messrs Trimnell, Cox, and Davison of Woldingham, Surrey. After some modifications to the final design, the library was built by Messrs Bagnall Bros of Wakefield under the direction of a Mr. Billington. The façade was built using stone from Crosland Moor, a district of Huddersfield, 14 miles from the building’s location. Henry Childe, then in his second term as Mayor, laid the foundation stone on February 15, 1905, the same day his wife unveiled the Queen Victoria statue in the Bull Ring.

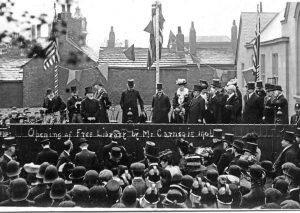

Andrew Carnegie opens the Drury Lane library in Wakefield. Image: Wakefield Libraries

On 2 June 1906, Andrew Carnegie made a brief visit to Wakefield to formally open the new library. Thousands of people gathered to witness the opening of the new building, which featured a Newsroom, Magazine Room, Lending Library and Reference library. It was first opened as a closed-access library, meaning that the public where not allowed to pick books directly from the shelves, but instead pick from a catalogue, with the librarians retrieving the publications. After this became hard to maintain, it became open-access in 1912.

On the opening celebration, a collection of 2,000 books and pamphlets relating to Wakefield, or which had been written by Wakefield men, was donated to the library by a local man, Charles Skidmore (1839-1908), then Bradford’s Stipendiary Magistrate. His collection laid the foundation of the present local history collection. The first city librarian was George H. Wood, who remained in the post for 32 years. From its beginnings, access was very important, and the library had braille books for the benefit of blind/partially sighted readers (Hutchings, 1981).

Due to the library’s popularity, in 1935 a new extension to the Lending Library was opened, along with a store and workroom in the basement. Soon after, a heating system was installed. A couple of years later, in 1939, the Junior Library was opened. In 1940 a new city librarian was appointed, Mr R. C. Sayell, who had been deputy librarian in Wakefield at that time. During the Second World War, paper was rationed, which made it impossible to purchase new books. Many of the library tiles had worn out and were discontinued – although in 1949, the library was very popular with a recorded 432,799 issues that year.

In the 1950s, at its peak, the annual book issue was still over 400,000, and the library had 13 team members working there. A major refurbishment took place in 1956 to make the library more accessible. Bookshelves were moved away from entranceways and lowered to make them more reachable. As part of a road widening scheme, a long wall in front of the library was demolished, opening the library more to the public by making it more visible.

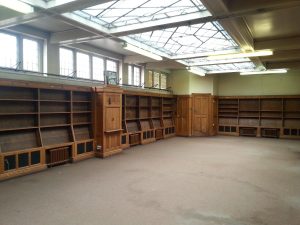

The lending library before renovation in 1956. Image: Wakefield Libraries

In 1962, the new Gramophone Record Library was opened. In 1967 the library won the Winston Churchill Award for National Library Week for its engagement programmes. During this time the city librarian Norman Willox, deputy librarian Brian Pearson and Councillor J Deen (Chairman of the library Committee), organised several events, such as a literary-themed dinner party at the Town Hall, and exhibitions to celebrate. Towards the end of the 1960s, the Reading Room as it had been renamed (originally Newsroom) was closed and changed into an exhibition space.

In 1981 the library celebrated its 75th birthday, and Norman Willox retired in the same year. During the mid-1980s, the Junior Library was incorporated into the main part of the building. That space became known as the Add-Lib gallery, a room that was rented out to local groups, and housed exhibitions. In 2003 the library was given 23 new computers, allowing the public to access the Internet free of charge, and a Wakefield Toy Library was launched, allowing local children’s groups, and eventually, individuals to loan out toys.

In 2004 plans were approved for the building of a new central library, combining Balne Lane and Drury Lane Libraries, although it never got built.

In 2006, celebrations took place to celebrate the library’s 100th Birthday, with staff dressing in Edwardian costumes, and a cake design competition was held, with the winning design baked by local bakers Hoffman’s.

However, in 2011, a new location for the library was found in the new Wakefield One Civic Office building, and the Carnegie Library ceased to be used as a library in 2012.

In 2014 plans began to redevelop the space into artists’ studio spaces and gallery, extending the adjacent Art House, which had built a new arts building a few years prior next door.

The Art House – Extension into the old library

In May 2014, The Art House began work on a £3m conversion project to turn Wakefield’s Grade II listed Library into 34 new artists’ studios, public spaces and more.

The construction team worked hard to carefully provide an incredible job refurbishing the original features of the Drury Lane Library. The library’s original skylights were removed and restored, and its beams re-painted in historical green. Hidden under grubby carpets over 30 years old, parquet flooring was uncovered, repaired and polished.

After years of being covered up under 16 coats of shockingly bright primary paint, the stunning original tiles of the library were discovered. The shockingly bright primary-coloured paint used on the walls was removed to reveal. These beautiful hand-painted original ceramic tiles were revealed and restored.

The original book lift was kept in its original position. The lift was manufactured by Waygood and Otis, and installed in 1935 when the library extension was built. The local library services have acknowledged the existence of other later book lifts within the district but it would seem that this one is fairly unique because it’s on show and decorated in a period style, and thought to be the only one of its type in Yorkshire. The original radiators were repainted and re-installed. Many of the bookcases were removed and sold, with some of them remaining in the space, and in the Art House Coffee Shop to act as a feature and reminder of the space’s original use.

In 2015 The Art House extended into the beautifully refurbished Grade II Listed Carnegie Library. The redevelopment added 34 new studios, communal areas and a gallery space.

The original blue-green tiles can also be seen in the room that was once the Reference Library. The use of faience or glazed tiles in Carnegie Libraries, as well as other public buildings of the era, was very common. It was a popular choice of finish for its decorative and hygienic properties. It is suggested that the prevalence of this green-coloured tile is partly explained by their being particularly recommended for libraries and other educational buildings as the colour was believed to prevent eye strain. This room now acts as a beautiful temporary exhibition space, called the Tilled Gallery.

The use of these tiles went much further than decoration and for the ease of cleanliness. Carnegie often made his philanthropic donations to heavily polluted industrial towns. From these often dull, smoky environmental settings, the importance of creating easy and natural lighting quickly developed into architectural examples for light’s presence in Britain’s libraries. It was common for briefs to include that the surface below a dado on the walls should be tiled in green glazed bricks as recommended in “helping to diffuse the light”, due to it absorbing very little and least trying on human eyes. The consideration of stone was also a deciding factor in tackling issues with light. As seen with many of the 660 Carnegie libraries in England, contrasting brickwork is a common use. The use of light stonework, such as stone from Crosland Moor used for the Drury Lane Library, supports the idea that the position and appearances of these new libraries with contrasting stone and brick, tall windows, and high cupola, indicate that in civic terms, the library service was to be viewed as a source of illumination.

The features seen in the Tiled gallery, are common in rooms used for Reference library rooms. Their concrete beams create a barrel vault, with its foliate decoration with bows and swags, to support the idea that Reference Library rooms should always regarded as a grand drawing room – an idea that is maintained in guidance for library design today, and that a modern public library should be conceived as the ‘living room of the city’.

The tiles that can be seen in the Studios in the former Drury Lane Library, which had been uncovered under 16 layers of paint and restored, also reflect the aesthetic choice of the times. The revealed and restored tiles are of the style of the ‘Damascus School’, which had a huge influence on the Arts and Crafts Movement, which aimed to change the values of society, turning away from cheap, poor-quality and mass production and reviving the values of decorative art and crafts.

In the 19th century, there was a great interest in the Middle East among collectors searching for ancient artifacts. The Middle East provided a wealth of inspiration, particularly in Islamic tile production, which flourished during the16th and 17th centuries. These tiles were created in large quantities to adorn the interiors of mosques and other significant structures with symmetrical designs featuring stylized flowers.

Even though the Damascus School of pottery was not considered as significant as Iznik pottery and the master potteries in Turkey, the tiles of Syria and especially Damascus tiles of the Ottoman Empire were more easily accessible to Western collectors in the 19th century. These tiles found their way into major collections and museums in Europe and America, catching the attention of key people in the Arts and Crafts Movement such as William Morris, John Ruskin and William de Morgan.

Although the Arts and Crafts movement was influenced by Islamic decorative art in their designs, it was specifically the ‘Damascus School’ tiles which were the most influential and fashionable. By the late nineteenth century, the copying of this style, and their widespread use were used for the interiors of hospitals, railway stations and ships as well as smoking rooms in houses and pubs.

These vibrant patterns were often decorated in cobalt-blue, turquoise and green on a white ground with flowers including carnations, prunus, and tulips surrounded by spiky leaves, and floral interlace flowerhead motifs. The tiles on display in the studio have been a source of inspiration for many artists and designers at The Art House.

Designer Ellie Way produced textile designs based on these original tiles, creating gorgeous hand-screen printed fabric that was then used to upholster chairs for our Coffee House and products available to buy in the Shop.

Image: Wakefield Libraries

The library’s exterior before (left) and after (right) the 1956 renovations. Image: Wakefield Libraries

Drury Lane Library in the 1970s.Image: Wakefield Libraries

75th-anniversary celebration for Drury Lane Library. Image: Wakefield Libraries